Story and Photos by Rick Browne

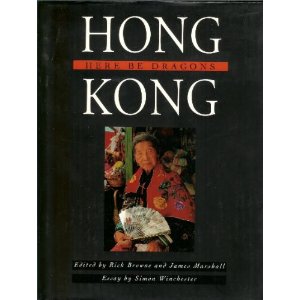

Hong Kong is one of my favorite cities on earth, having traveled there more than 18 times over the years. I enjoyed three months of living there while I worked on a photojournalism book about the island and its people, entitled Hong Kong: Here Be Dragons. That time was spent eating the best Chinese food on earth, traveling through Hong Kong’s twisted maze of streets, alleys and back roads, and experiencing one of the most dynamic and frenzied cities imaginable.

Hong Kong is one of my favorite cities on earth, having traveled there more than 18 times over the years. I enjoyed three months of living there while I worked on a photojournalism book about the island and its people, entitled Hong Kong: Here Be Dragons. That time was spent eating the best Chinese food on earth, traveling through Hong Kong’s twisted maze of streets, alleys and back roads, and experiencing one of the most dynamic and frenzied cities imaginable.

Racing Dragons in the Fragrant Harbour

Racing Dragons in the Fragrant Harbour

I first went there on assignment to cover the Hong Kong International Dragon Boat Races. The annual races feature dozens of long dragon boats (sort of a long canoe, with—of course—a dragon’s head and tail) racing across part of Hong Kong’s harbor. Described colorfully as “Fragrant Harbour,” the waters give Hong Kong its nickname.

The city’s streets, roadside food carts, night-and-day markets, and chaotic pace are energizing and exciting. The City Market, where residents and restaurateurs go for culinary raw materials, is one of the most fascinating sights in the city. It’s not for the weak of stomach, however; animals are slaughtered and prepared right on the premises, then hung on display for hungry shoppers. One morning as I was photographing the market, I watched a man force-feeding pigeons by dipping his face into a bucket of water mixed with wheat, taking a mouthful, then blowing it into the birds’ forced-open beaks, as if he were doing CPR. Through an interpreter, he explained that they were too nervous to eat, and that this helped keep them alive until they were sold. Also (he whispered), bellies full of grain and water made them heavier, so he could charge more.

And everywhere in Hong Kong is food, glorious food. There are Chinese (naturally) restaurants on every block, as well as eateries representing just about every country on earth. But the magic here is in the variety of Chinese restaurants, which cook in the styles of all the regions of China, using techniques both ancient and very modern. For the intrepid adventurer these restaurants can be a bit daunting—chicken entrails and skin, snails, frog legs, duck tongues, and other items we don’t even think of eating are presented on plates along with the more familiar noodles, meat, and leafy veggies. But for heaven’s sake try everything; you may be surprised by a delicious new taste…or perhaps not!

And everywhere in Hong Kong is food, glorious food. There are Chinese (naturally) restaurants on every block, as well as eateries representing just about every country on earth. But the magic here is in the variety of Chinese restaurants, which cook in the styles of all the regions of China, using techniques both ancient and very modern. For the intrepid adventurer these restaurants can be a bit daunting—chicken entrails and skin, snails, frog legs, duck tongues, and other items we don’t even think of eating are presented on plates along with the more familiar noodles, meat, and leafy veggies. But for heaven’s sake try everything; you may be surprised by a delicious new taste…or perhaps not!

One of the oldest methods of cooking with fire involves the use of a fire pot, which dates back to the invention of iron pots and cauldrons. There is evidence that fire pots were in use at least 10,000 years ago, but in those cases the pots were used to carry hot embers from camp to camp so that the nomadic people always had fire available. The use of these pots to actually cook food began in the Tang Dynasty, 618-906 A.D.

Hanging Out at the Hot Pot

Hot Pot, or Huoguo, is a traditional Chinese meal that is usually shared by a group. It’s the great, great, great grandfather of our present fondue, and if you want to stretch it a bit, the barbecue grill. There are several varieties of fire pots still in use today, especially in Chinese restaurants in Hong Kong and on the Chinese mainland. Some cooks hang a pot over a fire—much as our Colonial ancestors did—while others pour hot coals into a specially constructed pot: the coals sit in a chimney in the center of the pot and heat liquid in a surrounding chamber.

Folks sit around the hot pot, where they collectively cook meat (primarily thinly sliced chicken, fish and occasionally pork) and vegetables. In some cases each person has a wire or a bamboo basket, so they can individually cook their own food in the boiling water. The cooked food is then dipped into sauces and eaten. The resulting broth is a delicious elixer flavored by the various meats and vegetables that have been cooked in it. Tofu and/or noodles are sometimes added, and the soup is also shared.

The pots themselves, sometimes called steam boats, were originally made from iron, thereby providing a source of nutritional iron to the people who cooked with them. Today iron is still the most popular metal, but stainless steel (and even electric) hot pots can be found in use, especially in the larger cities. In rural areas you can still find traditional fire pots on tables and hearths. The live coals used to fire hot pots in early times have gradually given way to propane tanks, which are usually situated below the table where the hot pot rests.

There are as many kinds of hot pot recipes as there are dialects in China, as every region has its own style, using local ingredients: mala huoguo features a numbingly spicy broth; suancai yu huoguo consists of pickled greens with fish. There are hot pots that feature wild mushrooms, soft shell turtle, pork spare ribs, fish balls, and even a style that cooks up yak, the meat from China’s heritage cattle.

Dipping sauces and condiments span the breadth of flavors: salty XO sauce is made from chopped dried local fishes and shellfish, cooked with chiles, onion, garlic and oil. Sweet sauces like hoisin and tian mian jiang are made from sweet potato, wheat or rice, cooked with vinegar, sugar, salt, garlic and, you guessed it: chile peppers. Other bases for dipping sauce include soy sauce, sesame oil or paste, rice wine, coriander, vinegar and Chinese barbecue sauce. Some chefs even add an egg yolk or two.

Hong Kong Fire Pot

Here is a slightly “Americanized” recipe borrowed from a friend who lives in Hong Kong’s Central District. If you can’t find some of the ingredients in your local grocery store go to an Asian store, and they’ll probably have everything you need.

1 gallon of chicken, beef, or vegetable broth, or water

2 pounds spinach, washed and roughly chopped or ripped

1 medium to large Napa cabbage, washed and roughly chopped

1 cup Chinese broccoli, chopped into 1-inch pieces

1 lb. cleaned clams

1 to 1½ pounds large shrimp, shelled, deveined and slit on one side

1 pint carton of button mushrooms, cleaned and cut in half

2 to 3 ounces cellophane (mung bean) noodles, soaked in warm water and drained

2 boxes firm tofu, cut into 1-inch cubes

1 to 2 pounds beef eye round, sliced paper thin across the grain (or brisket or flank steak)

Place the broth in a large soup or stockpot and bring to a boil. Add the vegetables first, cooking until just beginning to soften, and then add the clams, shrimp, mushrooms, noodles, and tofu, finally add the beef and cook just until it turns brown. The whole process shouldn’t take more than 10-15 minutes.

Let your guests help themselves to the ingredients, serve up bowls of steamed rice, and have soup bowls handy so guests can drink the remaining broth at the end of the meal.

Serves: 6-8, more if they are light eaters

Garlic Dipping Sauce

2 tablespoons warm Japanese rice vinegar

1 tablespoon minced garlic

1 tablespoon sugar

Combine all ingredients, stir, and serve in a small bowl.

Makes ¼ cup of sauce.

Chili Dipping Sauce

1 tablespoon hot water

1 tablespoon Chinese chili sauce

1 teaspoon unseasoned Japanese rice vinegar

½ teaspoon sugar

Combine all ingredients, stir, and serve in a small bowl.

Makes ¼ cup of sauce.

XO Sauce

According to Wikipedia, the name XO sauce comes from fine XO (extra-old) cognac, which is a popular Western liquor in Hong Kong and considered by many to be a chic product there. In addition the term XO (pronounced “iks oh”) is often used in the popular culture of Hong Kong to denote high quality, prestige, and luxury. In fact, XO sauce has been marketed in the same manner as the French liquor, using packaging of similar color schemes. Its spicy flavor is used in stir-fries to spice up meat, seafood, tofu, and vegetable dishes. Stir-fried Lobster and Vermicelli with XO sauce is on the menu at the Dynasty Restaurant in Green Brook, New Jersey, while chefs at Tokyo’s Park Hyatt Hotel have decided XO sauce is the perfect accompaniment for Stir-fried Noodles with Chicken and Shrimp. Note: This recipe requires advance preparation.

½ cup dried small scallops (conpoy)

½ cup dried small shrimps (ha mei)

1½ cups peanut oil

15 dried red chiles, such as piquins

5 small shallots, sliced

3 cloves garlic, finely chopped

¼ cup minced ham

2 teaspoons sugar

½ teaspoon salt

3 tablespoons oyster sauce

½ teaspoon MSG (optional)

½ cup previously fried shallots

Soak the dried shrimps and scallops in different bowls for 6 hours or overnight.

Drain the dried shrimps and place in a blender and pulse to chop them coarsely. Tear the scallops in fine shreds with your hands. Then place them in a pot and bring it to boil. Turn off the heat, strain the scallops, and and squeeze out the water. Place the dried chiles in a blender or spice mill and pulse to chop them finely. Set aside.

Heat a wok and fry the shrimps for a minute and then scallops. Fry them until lightly golden and then add in the chiles. Fry for a minute and then add the shallots, garlic, and ham. Fry this mixture until the mixture is fairly dry.

Add the salt, sugar, MSG, and the oyster sauce. Now add in the previously fried shallots. Turn heat lower and stir until brown. Do not overcook as the scallops and shrimps will be too dry. Add small amounts of the XO sauce to taste to whatever stir-fry you are making.

Otherwise, let it cool completely then refrigerate. This can be kept in the refrigerator for about a month.

Yield: About 3 cups

Heat Scale: Hot

Note: Lee Kum Kee makes XO sauce that can be ordered from WeRGourmetFoods.com.

Latest posts by Mark Masker (see all)

- 2024 Scovie Awards Call for Entries - 07/07/2023

- 2024 Scovie Awards Early Bird Special: 3 Days Left - 06/29/2023

- 2024 Scovie Awards Early Bird Deadline Looms - 06/25/2023