By Anon.

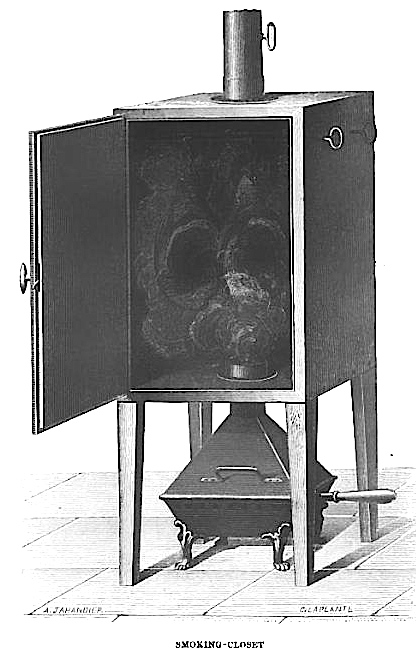

I hadn’t realized that the French were also leading the way for grilling advances in the latter half of the nineteenth century until I read this article, and the one by Chef Jules Gouffé. Gouffé loved his smoke, but this author eschews it and prefers smokeless grilling. Then again, this author is set on serving the meat rather than preserving it. The illustration is a French Smoking Closet, 1871.

Returning to the grilling apparatus, we shall possibly surprise many by avowing that, in our opinion, the French beat us as much in this respect as in many others. That they succeed in soups, sauces, and entrees, is undoubted, and copper saucepans go for much therein; but for the cuisine bourgeoise (household cooking) we should indicate grilling as the point where they are more entirely successful than we are. Here charcoal or braise (a form of charcoal), as the fuel, gives the French cook an advantage. It enables him to serve up fish, flesh, and fowl, cleanly grilled, not smoke-flavored, and the sauce, if sauce there be, has nothing to interfere with its due appreciation. The English cook, as a rule, appeals to the frying-pan and produces her cutlets, often sodden, and generally tasteless, with small idea that meat and its flavor is one thing, and the sauce appropriate to it another. When cutlets have been cooked in this fashion, the tenant of the dining-room learns that delicate tender mutton exists no more; leather, for all practical purpose of taste, might replace it. Yet how could we expect an English cook with the ordinary coal-fuel range to have a bright fire just ready for grilling at the moment when the entree of cutlets should be served? The charcoal or braise embers, being a contrivance apart, are, with a slight use of the bellows, always ready for the grill. Speaking not dogmatically, but with conviction, we place charcoal or braise, as a grilling element, as of the first necessity in a range where due justice is to be done by the cook. Nor can we believe that this suggestion is one necessarily attended with inordinate expense. It sufficeth to put—if Count’s plan above mentioned is attended with difficulty—in modern close ranges a fifteen-inch square grate, sunk some three inches below the level of the top, with a regulator for the draft from without, so that the charcoal or braise shall burn freely; and we venture to say that the cost of the charcoal will be saved in the butcher’s bill, to say nothing of the temper of the master, suffering under the infliction of meat wrongfully bedabbled in cinders and begrimed with coal-smoke! Let it be taken as a gastronomical observation of supreme importance to the seeker after culinary truth, that the eminence of French cookery does not lie solely in soups or sauces, but in the cleanliness with which fish, flesh, and fowl are grilled, aided by the perfectly made sauces, separately cooked, with which such flesh and fowl are served. Not, however, that bread-crumbed cutlets are always out of place, but that the importance of clean grilling should be more clearly recognized. And let no one here cite the advantage of Dutch ovens, or similar contrivances, for avoiding the coal smoke. They are aids to the idle, but fail in the essential application of direct heat and oxygen to the meat. Of course clubs and large establishments can afford to keep a coke-grill constantly going, and to them coke is cheaper, and, well kept up, as effective as charcoal; but in the small establishment the cook, seeking to grill, is confined to her coal-fire, and such use as she may make of it.

Returning to the grilling apparatus, we shall possibly surprise many by avowing that, in our opinion, the French beat us as much in this respect as in many others. That they succeed in soups, sauces, and entrees, is undoubted, and copper saucepans go for much therein; but for the cuisine bourgeoise (household cooking) we should indicate grilling as the point where they are more entirely successful than we are. Here charcoal or braise (a form of charcoal), as the fuel, gives the French cook an advantage. It enables him to serve up fish, flesh, and fowl, cleanly grilled, not smoke-flavored, and the sauce, if sauce there be, has nothing to interfere with its due appreciation. The English cook, as a rule, appeals to the frying-pan and produces her cutlets, often sodden, and generally tasteless, with small idea that meat and its flavor is one thing, and the sauce appropriate to it another. When cutlets have been cooked in this fashion, the tenant of the dining-room learns that delicate tender mutton exists no more; leather, for all practical purpose of taste, might replace it. Yet how could we expect an English cook with the ordinary coal-fuel range to have a bright fire just ready for grilling at the moment when the entree of cutlets should be served? The charcoal or braise embers, being a contrivance apart, are, with a slight use of the bellows, always ready for the grill. Speaking not dogmatically, but with conviction, we place charcoal or braise, as a grilling element, as of the first necessity in a range where due justice is to be done by the cook. Nor can we believe that this suggestion is one necessarily attended with inordinate expense. It sufficeth to put—if Count’s plan above mentioned is attended with difficulty—in modern close ranges a fifteen-inch square grate, sunk some three inches below the level of the top, with a regulator for the draft from without, so that the charcoal or braise shall burn freely; and we venture to say that the cost of the charcoal will be saved in the butcher’s bill, to say nothing of the temper of the master, suffering under the infliction of meat wrongfully bedabbled in cinders and begrimed with coal-smoke! Let it be taken as a gastronomical observation of supreme importance to the seeker after culinary truth, that the eminence of French cookery does not lie solely in soups or sauces, but in the cleanliness with which fish, flesh, and fowl are grilled, aided by the perfectly made sauces, separately cooked, with which such flesh and fowl are served. Not, however, that bread-crumbed cutlets are always out of place, but that the importance of clean grilling should be more clearly recognized. And let no one here cite the advantage of Dutch ovens, or similar contrivances, for avoiding the coal smoke. They are aids to the idle, but fail in the essential application of direct heat and oxygen to the meat. Of course clubs and large establishments can afford to keep a coke-grill constantly going, and to them coke is cheaper, and, well kept up, as effective as charcoal; but in the small establishment the cook, seeking to grill, is confined to her coal-fire, and such use as she may make of it.

From: Littel’s The Living Age, Fifth Series, Volume 18, April-June 1877.

An excerpt from First Skin 500 Squirrels: Eyewitness Accounts of Barbecue History by Dave DeWitt. Order the book here.

Latest posts by Dave DeWitt (see all)

- Enchiladas Verdes con Chile Pasado - 02/08/2023

- Smoked Oysters with Ancho Chile Sauce - 01/13/2023

- Machaca Sierra Madre - 01/11/2023