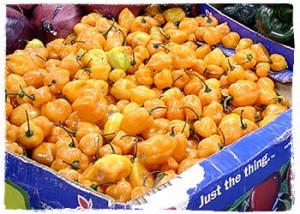

Pepper seeds were carried and cultivated by Native Americans as the chinense species hopped, skipped, and jumped around the West Indies, forming—seemingly on each island—specifically adapted pod types that are called “land races” of the species. As we have seen, each land race gained a name in each island or country, although the term “Scotch bonnet” is used generically throughout the region. The pods of these land races became the dominant spicy element of the Caribbean, firing up its cuisines—and its legends.

A well-known West Indies folktale describes a Creole woman who loved the fragrant island pods so much that she decided to make a soup out of them. She reasoned that since the Scotch bonnets were so good in other foods, a soup made exclusively of them would be heavenly. But when her children tasted the broth, it was so blisteringly hot that they ran to the river to cool their mouths. Unfortunately, they drank so much water that they drowned—heavenly, indeed! The moral of the story is to be careful with Scotch bonnets and their relatives, which is why many sauce companies combine them with vegetables or fruits to dilute the heat.

A Caribbean natural pepper remedy supposedly will spice up your love life. In Guadeloupe, where chinense is called le derriere de Madame Jacques, that pepper is combined with crushed peanuts, cinnamon sticks, nutmeg, vanilla beans packed in brandy, and an island liqueur called Creme de Banana to make an aphrodisiac. We assume it’s taken internally.

An old island adage says that the best Caribbean hot sauce is the one that burns a hole in the tablecloth. We’ve never seen that happen in all our trips to the Caribbean, but we’re certain that the earliest hot sauces in the region were made with the crushed chinense varieties. According to some sources, the Carib and Arawak Indians used pepper juice for seasoning, and after the Europeans “discovered” chile peppers, slave ship captains coming from Africa combined pepper juice with palm oil, flour, and water to make a “slabber sauce” that was served over ground beans to the slaves aboard ship.

The most basic hot sauces on the islands have traditionally been made by soaking chopped Scotch bonnets in vinegar and then sprinkling the fiery vinegar on foods. Over the centuries, each island developed its own style of hot sauce by combining the crushed chiles with other ingredients such as mustard, fruits, or tomatoes.

Homemade hot sauces are still common on the islands of the Caribbean. The sauces piquante and chien from Martinique and ti-malice from Haiti all combine shallots, lime juice, garlic, and the hottest chinenses available. Puerto Rico has two hot sauces of note: one is called pique and is made with acidic Seville oranges and habaneros; the other is sofrito, which combines small piquins (“bird peppers”) with annatto seeds, cilantro, onions, garlic, and tomatoes. In Jamaica, Scotch bonnets are combined with the pulp and juices of mangoes, papayas, and tamarinds. The Virgin Islands have a concoction known as “asher,” which is a corruption of “limes ashore.” It combines limes with habaneros, cloves, allspice, salt, vinegar, and garlic.

Another good example of the combination of habaneros and other ingredients is Melinda’s (called Marie Sharp’s Hot Sauce in the United States), made in Belize from habaneros, carrots, and onions, which makes for a milder, more flavorful sauce than simply combining the pureed chiles with vinegar.

Jamaica’s Pickapeppa sauce has a flavor similar to Worcestershire sauce and only a slight bite. Its fruity flavor comes from mangoes, raisins, and tamarind. However, it should be noted that the company also sells a much hotter version of Pickapeppa with more Scotch bonnets and less fruit.

Another famous Caribbean hot sauce is Barbados Jack, which has been produced by the Miller family of Barbados since 1965. It consists of Bonney peppers, mustard, turmeric, and onions, and is commonly served over seafood and poultry dishes. According to Caribbean expert Chelle Koster Walton, “The Millers began by selling ladiesful to neighborhood customers at the rate of thirty gallons a week. Eventually the Millers poured their sauce into recycled soda bottles and rum flasks, and distributed them around town by bicycle.” In the late 1980s, their production was up to 1,900 gallons of Barbados Jack a week.

The hot sauce called Matouk’s owes its existence to a speech by Trinidadian political leader Dr. Eric Williams, who said that the variety of jams, jellies, sauces, and pickles made by housewives were an integral part of Trinidad’s culture. However, he pointed out that as women gained employment, the nation was in danger of losing the tastes of the home kitchens of Trinidad and Tobago. George Matouk, a Trinidadian businessman, was inspired by Williams’s speech, and in 1968 he founded Matouk’s Food Products and began manufacturing traditional-style jams, jellies, and hot sauces. To make the hot sauce, which is available in three heat levels, Congo peppers (the local name for habaneros) are combined with herbs, spices, and papayas. About half of the Matouk’s sauce production is consumed locally, and the rest is exported, with the United States as the number-one market for Matouk’s Trinidadian hot sauces.

Editor’s Note: This originally ran in Dave DeWitt’s The Habanero Cookbook, which you can find here.

Latest posts by Mark Masker (see all)

- 2024 Scovie Awards Call for Entries - 07/07/2023

- 2024 Scovie Awards Early Bird Special: 3 Days Left - 06/29/2023

- 2024 Scovie Awards Early Bird Deadline Looms - 06/25/2023